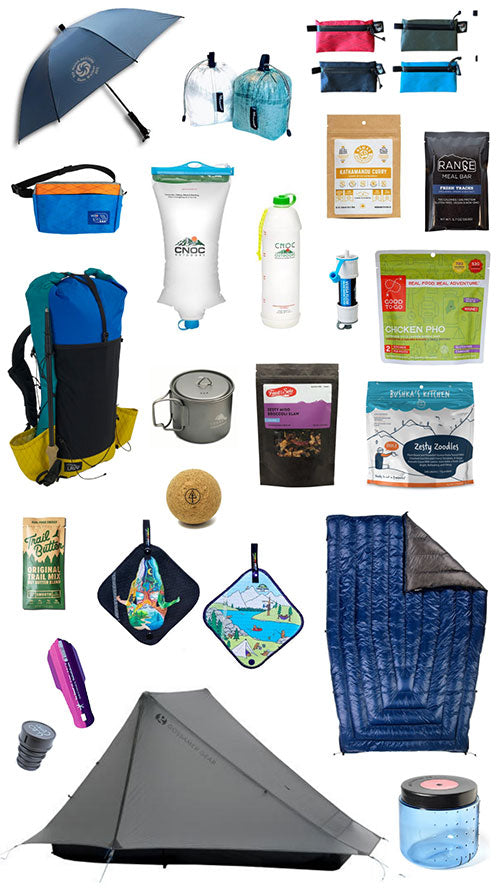

Editor’s note: this article originally appeared on SlingFin’s blog. We’re thrilled to share an edited version here with permission.

Tents have it pretty rough. Their purpose is to keep you protected from the elements, so by definition, they’re exposed to nature’s fury. Season after season, your trusty tent or tarp is subjected to wind, rain, dust, snow, hail, animals, and (sometimes) careless users. But for a shelter that has been treated well over the years, the thing that will eventually kill it is something you might not expect: the sun.

In addition to visible light, the sun emits a massive amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which has a shorter wavelength than visible light and is present wherever there is sunlight. While inorganic materials (like silicone and metal) are largely unaffected by UV radiation, organic compounds (i.e., anything containing carbon, not just your fancy kale) can be damaged by exposure to UV. This includes all organic polymers, whether synthetic (like nylon and polyester) or naturally occurring (like cotton and wool).

Synthetic polymers (e.g. all plastics) are ubiquitous in the tent world. By the time modern geodesic tents hit the scene in the 1970s with the North Face Oval Intention, pretty much all technical lightweight tents were made of synthetic polymers, usually nylon or polyester.

Historically, nylon has been far more popular, with polyester relegated to the realm of low-end price point tents. Recently, however, a new crop of high-end shelters has emerged using higher quality polyester, which has become popular for its ability to retain its shape when wet and its reputation for superior UV resistance. (For some deeper background, check out SlingFin’s tent fabric article).

Synthetic Polymer Chemistry

Now, let’s hold our noses real quick for a bit of chemistry. It’ll be over soon, I promise. Polymers are large molecules (called macromolecules) composed of chains of smaller components called monomers. These monomers are linked together in chains held together with different types of chemical bonds.

In nylon, these are called amide bonds, which is why nylon is also known as polyamide. Polyester is similar in that it is made of monomers linked by ester bonds. Poly-amide, poly-ester… get it? I really thought I would never have to think about this again after I ditched pre-med, but I just can’t seem to escape organic chemistry entirely.

UV radiation breaks down the bonds between these monomers, leading to the disruption of the macromolecules. In practice, this means nylon and polyester fabrics become brittle, weak, and unsuitable for use in tents. Fabric left exposed to sunlight for too long starts to look, feel, and tear like tissue paper.

Study Goals: Effects of UV on Tent Fabrics

While it has been generally accepted by the outdoor industry that polyester has better UV resistance than nylon, the experimental evidence supporting this comes predominantly from other industries and generally involves much heavier fabrics in a variety of bizarre testing conditions. We haven’t been able to find any studies directly examining the effects of sun exposure on the lightweight fabrics used in outdoor equipment.

So in the interest of making informed design decisions, we here at SlingFin decided to conduct our own dubiously scientific tests to investigate the effect of UV on tent fabrics. We wanted to know just how big of a role UV plays in a fabric’s lifespan, and what other factors contribute to a fabric’s UV resistance, like weight, coating, and fabric type.

From our experience making tents, we know that UV is the only thing that will inevitably kill a properly cared-for tent (as long as you didn’t buy a tent with PU-coated fabrics), but we wanted to know just how quickly that destruction takes place.

Is UV really all that much of a factor in tent lifespan? How much do you have to use a tent for it to get UV-cooked? Is polyester really better than nylon, and if so, by how much?

Experimental Design and Data Collection

The primary goal with our experimental design was to find a way to compare fabrics side-by-side in the same conditions, and to reveal broad trends in how fabrics react to UV exposure. These tests are not to any standard, ASTM or otherwise, so we caution against extrapolating these results too broadly.

The purpose of this experiment was to compare a variety of fabrics to each other, some field-proven and some new, to inform SlingFin’s fabric selection and tent and tarp design process.

To begin, we had to design our testing facility. We wanted our testing to simulate real-world conditions as closely as possible. Since we don’t have access to an ASTM-compliant UV testing facility, and since we do have a nice roof above our design studio, we decided to put the fabrics outside and let the sun do its thing — a better simulation of real world tent use anyway.

We assembled some industrial racking, oriented southwest for maximum daily sun exposure. We sewed together panels of up to six fabric swatches, all side-by-side and facing the same angle.

To measure the damage to the fabrics, we selected tensile strength as a benchmark because it’s reproducible, accurate, and easily quantifiable. Tensile strength is defined as the maximum load that a material can support without fracture when being stretched.

After each test period, we cut a 12” x 2” strip from each fabric and cut it into two 6” x 2” pieces. We then pulled the pieces apart in our lab and averaged the results to make our data point. Every few weeks, we cut another strip and tracked the fabric’s descent towards its inevitable demise.

The Results

The first thing we noticed when we started tearing fabric apart is that UV damage occurs rapidly to tent fabrics of all weights. After one month of exposure, all the fabrics except one exhibited a measurable drop in tensile strength, with losses ranging from about 5% to a whopping 47%.

After 100 days, all the fabrics (besides our three titanium dioxide-coated fabrics, which we’ll discuss later) had dropped below 70% of their original tensile strength, and most of the fabrics lighter than 40D (as well as some of the heavier fabrics) had lost over 50% of their strength.

The weathering was visually obvious as well. The colors faded, the whites turned yellow, and there was general discoloration.

Before and After

Day 0: So fresh, so clean.

Day 98: Not so much. Note that the white TiO2-coated fabric in the upper left is relatively unchanged.

Understanding the Data

It’s important to note that obviously, not all fabrics start out with the same tensile strength. A 50% reduction in strength may not be a big deal or it may render a fabric totally useless, depending on how strong it was to begin with.

To help visualize this, we made two graphs of the same data: one is each fabric’s tensile strength in pounds, and the other is each fabric’s tensile strength as a percentage of its original strength. When we talk about the rate of strength loss, we’re usually referring to the rate at which it loses strength compared to where it started.

When we say that a fabric is UV resistant, we mean that the rate of tensile strength loss is slow compared to its initial strength.

For example, after 208 days of UV exposure, a 300D polyester was tearing at around 64 lbs and the 10D nylon was tearing at around 32 lbs. However, the 10D started at 72 lbs (that’s exceptional for a 10D, by the way), meaning it experienced about a 65% loss compared to its original tensile strength, whereas the 300D started at a whopping 334 lbs, meaning it had lost 81% of its strength by the end of the test.

Thus, we say the 10D is much more UV-resistant than the 300D because it was closer to its initial strength, even though the 300D was still technically twice as strong by the end of the test.

OneUp on Shishapangma in Tibet. This particular tent was used heavily at high elevation in the Himalaya, came back to the US, did a tour of duty at Burning Man, and subsequently met its demise when a chunk of ice fell straight through the UV-cooked flysheet during a ski tour at Crater Lake in Oregon.

One way to increase a tent’s lifespan is to use a fabric that’s initially much stronger than it needs to be, so it will take longer to reach the point where the UV degradation becomes a functional issue. But at a certain point, very UV-resistant fabrics will eclipse less UV-resistant fabrics that started out stronger.

For instance, after about 150 days, the 10D nylon that I mentioned above actually surpassed the strength of all three of the 20D fabrics that we tested, as well as a 40D nylon that started out 76% stronger than the 10D. So while the 10D started out with a lower tensile strength, its UV resistance was so much better than the other fabrics that eventually the 10D was the strongest of the five.

Without further ado, here are the results:

Winners

There were a few fabrics that stood out for both good and bad reasons. Several fabrics performed surprisingly well; far better than their weight would suggest, whereas others significantly underperformed expectations. We’ll start with the overachievers.

The biggest surprise of our testing was the 10D*450T NY66 SIL/SIL, which is the flysheet fabric we use in the SlingFin Portal Tent, 2Lite Tent, SplitWing Tarp, and Flat Tarp. Generally, such lightweight fabrics have relatively poor UV resistance because the sun penetrates them more easily. However, our 10D nylon was exceptionally UV-resistant. It could be because it's a type 66 nylon, but the 40D NY66 that we tested did significantly worse, so it's hard to say exactly why our 10D did so well.

In terms of the rate of strength loss, it outperformed all the non-titanium dioxide coated fabrics. In terms of absolute tensile strength, by the end of our test period, it was actually stronger than several of the fabrics that started out with a higher tensile strength by virtue of its slow rate of strength loss.

The other top performers were titanium dioxide (TiO2) coated fabrics, which was not surprising as the UV mitigating qualities of TiO2 are well-established. Titanium Dioxide is a UV blocker commonly used in sunscreens and paints. This stuff is great, and has absolutely unbelievable UV resistance. It can be mixed in with some coatings specifically to increase their UV resistance, which is what we do with our LFD and BFD expedition basecamp dome tents.

The Everest climbing season is 2 to 3 months, during which the tents are left up continuously at between 15K and 20K feet in elevation, where the UV index is about 20% higher because of the thinner atmosphere. In other words, these are absolutely brutal conditions for tent fabric. Guides using our domes on Everest report getting 5 to 8 seasons of use out of our LFD and BFD dome tents. Other companies’ non-TiO2 coated domes generally last 1 to 2 seasons, according to those same guides.

The best performing fabric in our test was the ET70, which is a TiO2-coated 70D nylon. Unfortunately, we’ve had to move on from it because of supplier quality control issues. However, 250D TiO2-coated polyester ripstop is a great alternative we’re now using in our expedition domes — its tensile strength starts out so much higher that it takes about 460 days of exposure to reach the initial tensile strength of the ET70. That’s four seasons on Everest, even when adjusting for the higher UV index at altitude. Not too shabby.

Long story short, TiO2 coatings make a BIG difference. To visualize the effect of the TiO2 coating, compare the graph of the 250D Poly RS TiO2 with the 250D Poly RS without TiO2, which is the exact same fabric without a TiO2 coating. Notice a difference? Thought so.

Slackers

It wasn’t all fun in the sun, though. There were a few fabrics that on paper should have performed very well but failed to meet expectations.

The most egregious was the 300D solution-dyed polyester. 300D is quite heavy by tent standards, which usually translates to better UV resistance. Additionally, solution-dyed fabrics tend to do better against UV, because the yarn is dyed before the raw material is spun, meaning pigment fully permeates the yarns, making them less penetrable to UV. (For the same reason, darker fabrics tend to be more UV-resistant because they're less penetrable to light.) Add to that polyester’s reputation for UV resistance, and we were expecting the 300D solution-dyed polyester to be a top performer.

However, it lost a whopping 38% of its tensile strength in the first month of testing alone. The only fabrics that lost more strength in that time were two lightweight 20D fabrics, a PE-coated nylon and a sil/PE-coated polyester. After 132 days, the 300D poly had lost almost 75% of its initial strength. By contrast, in that same time period, our 10D NY66 only lost about 37% of its initial strength.

The other biggest flop was the 20D*420T Poly RS sil/PE, which is a popular fabric in some “silpoly” shelters (even though it’s not sil/sil, more on that in our fabric coatings article). It lost almost half its strength in the first month, and after 104 days was down to only 14% of its original tensile strength. It was so bad by this point that we could barely get it into our tear tester intact, and it was easy to pierce with a finger. We call this “the finger test” — and when a fabric fails the finger test, it’s totally cooked.

20D*420T Poly RS sil/PE at the end of the testing period. Total devastation. Where did the rest of it go? The answer is blowin' in the wind.

Polyester vs. Nylon

Let’s compare the two worst-performing fabrics in our test, in terms of relative strength loss. One was the 20D*420T Poly RS sil/PE I mentioned above (polyester), and the other was the 20D*330T NY RS sil/PE floor fabric we use in our lightweight tents (nylon). Both started out at basically the same strength and have the same type of coating.

Compared to the nylon, the polyester performed slightly worse. The difference wasn’t big enough to say definitively that the nylon is more UV-resistant, but I feel pretty good about saying that there’s no significant increase in UV performance by switching to polyester.

My expectations for the polyesters were higher than for the nylons because of polyester’s widespread reputation for excellent UV resistance. Our findings may sound like a glaring indictment of all polyester, but there are some important caveats.

There is a lot of variation even between fabrics of the same spec; every fabric is an individual, so apples-to-apples testing is very hard, and we’re limited to whichever fabrics we’re able to get our hands on for testing.

Also, the type of coating seems to have an effect on UV resistance, and we didn’t have access to any sil/sil polyesters for testing. Generally, sil/sil fabrics outperformed comparable sil/PE fabrics, and all our polyesters were sil/PE, PU, or PE only.

So at this point, I wouldn’t go so far as to assert that nylon is more UV-resistant than polyester as a rule, but what is clear that polyester is not necessarily more UV-resistant than comparable weight nylon, at least at the weights and with the coatings typically found in tents.

It's safe to say polyester’s blanket reputation as a UV heavyweight seems to be overhyped.

Nylon 6 vs. Nylon 66

Generally, we prefer nylon 66 to nylon 6 where feasible because of its lower water absorption and increased abrasion resistance. Also, our anecdotal experience has been that nylon 66 tends to perform better in UV than nylon 6, but the results of this round of testing are inconclusive.

We only tested two varieties of nylon 66 in this test, our incredible 10D and a 40D, both with sil/sil coatings. The 10D (have I mentioned how great it is? It’s really great!) did unbelievably well, whereas the 40D didn’t do as hot. However, the 40D used a slightly different formulation of silicone coating. Our current round of UV testing seems to be indicating that the coating composition is a bigger factor than the type of nylon.

Based on the results of our first round of testing, it’s hard to say with any confidence if there’s a practical difference in UV resistance between nylon 6 and nylon 66; though we’ll have more results in a few months that will hopefully provide more conclusive data.

Coatings and UV Resistance

As we note in our fabric coatings article, the waterproof coating that’s applied to the fabric has almost as much effect on the properties of the fabric as the fabric itself. This is true for UV resistance as well.

Our three lowest-performing fabrics were all sil/PE-coated (two polyesters and a nylon), rather than sil/sil. Since we pretty much only use PE coatings in our floor fabrics, UV isn’t a big factor, but it’s worth noting if you’re shopping for tents elsewhere, as most tent companies use sil/PU or sil/PE flysheet coatings.

By far the most significant variable as far as coatings are concerned was the presence or absence of titanium dioxide. The three clear winners in our testing all had TiO2 coatings. This is what we expected, since the TiO2 was added to the coatings specifically to increase their UV resistance.

To the best of our knowledge, no lightweight tent fabrics use TiO2 (it adds significant weight and cost to the coating), so for most people this won’t be an option in their tent purchasing decisions.

When deciding on a lightweight backpacking or mountaineering tent, a more likely scenario would be a choice between sil/PE or sil/sil flysheet fabric. We tested both a sil/sil and a sil/PE 20D nylon and the sil/sil nylon was clearly superior. Our bottom three performers were all sil/PE coated.

Takeaways

So, what does all of this mean for you in practical terms, and how can you mitigate the impact of UV damage on your tent to maximize its lifespan? Leaving these fabrics on the roof of our studio day in and day out is a pretty extreme scenario that (hopefully) is more than most tents will experience in their normal life, but the results can inform our tent selection, use, care and storage practices.

Your backpacking style plays a big role in the amount of UV your tent gets exposed to. If you tend to move camp every day, your tent will only be up during the day for a few hours, and it will be inside your pack when the UV index is highest in the middle of the day.

During a typical thru-hike, for example, you’ll only get an hour or two of sunlight on your tent a day, and those will be the mildest daylight hours in terms of UV exposure. In this kind of use, a typical 5-month PCT hike (and this is a very rough estimate, don’t @ me) might translate to one month’s worth of our testing (assuming 14 hours of daylight on average during our test and just under 3 hours of daylight tent time per day on a 150 day thru-hike).

Take into account cloud and tree cover (if you’re an AT hiker, that is) — and the fact that the UV index is often several times higher around solar noon than in the hours preceding and following it — and the chances are if you’re thru-hiking and moving camp every day, you’re probably going to break something else on your tent before your flysheet fails the finger test. But take too many zero days, or bring your tent on more than one thru-hike, and you’re into UV damage territory, meaning there’s a better chance that a gust of wind will rip your guy points off.

However, if you tend to hike into a basecamp and leave your tent set up for longer periods of time, especially at altitude, UV becomes much more of an issue. The most extreme example of this is expedition-style mountaineering, where basecamps can be left up for weeks or months at a time. This is why we spec TiO2 fabric on our expedition basecamp domes. But even in less extreme conditions, like backcountry ski trips or even backpacking trips where you camp for extended periods between moving camps, a few weeks of use a year adds up quickly when you’re leaving your tent set up all day.

The sneaky UV killer is improper gear storage. Even window-filtered sunlight has plenty of UV. If your living space is cursed with ample natural light, find a dark closet or use opaque bins for gear storage. Stick ‘em where the sun don’t shine.

The Bottom Line

UV exposure is only one of a slew of variables that determine how long your tent will last. Managing your tent’s exposure to UV is just another facet of being a good tent parent. Knowing how you plan to use your tent will help you determine how much UV resistance matters to you when making buying decisions.

10 comments

GGG Moderator

@ Janeen:

It could depend on how hot your garage/car gets at any given time more than anything else. UV might not be as much of a concern since your quilt is covering your gear. But what could make a difference is how hot & humid the climate is in the car. Also how you are storing the tents inside the car (crammed tent stuff sack? loose in a storage bin?) could have an adverse effect on the tent’s waterproof coating. Having a tent fly & tent body loose in a storage bin is much better for the coating than it being stuffed in a stuff sack all the time, and having them in excessively hot & humid conditions constantly (especially in a stuff sack) could impact the lifespan of the shelter coating. Tim might have more insights on this too!

Janeen Houghton

Hi wondering in general I’m planning to keep my 2 tents in my car which is kept garaged. I work nights so home by 9am. Is this going to speed up the deterioration of my new tents or is it ok. I have tinted windows and a quilt covering all my camping gear

RS

There’s no consistent trends in the fiber strengths and material types (except with and without TiO2 coatings) because each color, type of dye used, and dye concentration grants a factor of UV resistance. Even fabrics with qualitatively the same color saturation can require quite different concentration of dyes because the human eye is not equally sensitive to all colors. The strength of each fabric is also quite affected by humidity and waterproof coatings. If testing was done during higher relative humidity nylon would be impaired more than polyester for example (unless there were waterproof coatings involved). In addition, there are synergistic hydrolytic degradative effects from UV, humidity, and temperature history that affect all fabric types unequally.

As long as shadows are mitigated for and the tension clamps are loaded consistently, these tests are pretty good at determining the environmental degradation resistance of individual types of fabrics relative to each other, but no meaningful conclusions can be drawn with regard to just UV, humidity, or temperature effects. This is why material scientists create testing conditions to isolate for these synergistic variables. It would be interesting to see which color options have the best and worst environmental degradation resistance.

Gregor

What colour was each fabric?

Colours absorb and reflect uv light differently. That could be the answer to your surprising results. Red orange yellow will absorb more than blue indigo violet. The lighter the colour, the less u will be absorbed. Over time this may make a big difference I’m guessing.

Larry Freilich

Not mentioned, and maybe not an option, would be a fabric treatment. Nikwax makes a spray that supposedly imparts UV protection. Any comment?

SlingFin Tim

We haven’t done any testing on UHMWPE fabrics yet, but it’s on the list! UHMWPE itself is quite UV resistant, or so I’ve heard, but now I’m taking that with a grain of salt! My guess is that the weak point of DCF in UV will be the glue used to laminate the PET to the UHMWPE. We haven’t tested any woven Ultra, since it doesn’t make much sense for tents. But we have some Ultra TNT that we may test in the future!

Jean: Your tent is smelling because it’s coated with PU, which is hydrolyzing. It’s not the fabric itself, but the coating that is falling apart and giving off that distinctive old tent smell. Unfortunately, there’s no way to stop that process once it begins, and the hydrolysis also compromises the waterproofness of the fabric. Might be best to relegate that tent to fair weather use!

Bonfus: Yes, indeed! We certainly can’t say that nylon is better than poly in UV as a general rule, but we can confidently say that poly is not always better than nylon!

Alan W

UV resistance of synthetic organic polymers can be markedly improved by the addition of a few hundred ppmw of various commercial UV inhibitor additives, AntiOxidant additives, and most preferably by a synergistic combination of both types well mixed in the polmer before spinning yarn.

The point being that identification of the polymer type in the fabrics is far, far from being complete definition of fabrics in the experimental data.

For example, 2 nylon 6,6 base fabrics can have much different UV results if one is “barefoot” with no stabilizing additives and the other is loaded with a strong mix of UV and AO additives. Ditto for PET and other base polymers

In short, there is another set of variables (additive types and amounts), beyond simple polymer type.

No wonder anecdotal – and even experimental – views are all over the map.

Jean Janu

What about a lightweight backpacking tent (don’t know if poly or nylon) kept in dark covered bin in hot garage (AZ) that comes out stinking (no dead animals inside)? Is it the smell of the fabric disintegrating? Time to throw it out, not wash it?

Thanks. Jean

Walt

Very interesting. What about DCF and Ultra?

Bonfus

Extremely interesting article, that seems to suggest that the reputation that Poly has long had of having better UV resistance than Nylon may not be (always) true.