Editor’s Note: We’re incredibly excited to share this Q&A about a solo traverse of the Great Himalayan Trail High Route. Matthias completed the technical undertaking in right around 100 days, using a Bonfus pack and shelter! Read on to hear how the gear performed in one of the harshest, most challenging environments in the world — and to vicariously soak in some incredible stories and landscapes too!

Hello Matthias. Who are you and how did the idea of the Great Himalayan Trail High Route come to your mind?

Hi, my name is Matthias, I am a neuroscientist, working at a university. I am an ultrarunner, so I like to go fast and light for long distances. I also have some background as a climber/ alpinist.

I love maps and spend a lot of time at local map stores. I am totally fascinated that some places around the world are still not fully mapped out. One day I read a post online where people discussed how to cross a mountain pass in the Himalayas, struggling to find a safe route. Later, it turned out that the mountain pass was incorrectly labelled on the maps.

In Nepal, some of the mountains have many different names, and they differ between the local language and the “official” maps. I find it really exciting that with all the digital data available today, that there are still remote places where one can get truly lost. For me, this is in stark contrast to the European Alps, for instance, where it sometimes feels like every single trail has been marked and traveled a hundred times.

Once a friend gave me a book about two brothers who ran part of the lower route of the Great Himalayan Trail (GHT) in the 70’s. These guys were neither professionals nor sponsored athletes, but somehow managed their traverse with the help of local people and the right attitude. Super fascinating! After reading the book, I wondered if it was possible to adopt their style and move quickly at higher elevations.

Through the years the idea to hike the GHT grew in me and in 2022 I was finally brave and fearless enough to undertake the 1800 km journey.

This journey is known for being long and hard. How did you plan the route, resupplies and logistics?

I knew my trip across the Himalayas would take between 100 to150 days (it took around 100 in the end). Most people I talked to before the trip said that one would probably have to come back 2-3 times to Nepal to finish the entire route, as the weather window is relatively short, and also due to other logistical issues like visas and permits.

In Nepal, the ideal hiking season is very short. I started at the beginning of April, still in wintry conditions. In the past, some people have started even earlier; but around mid-March there is often still too much snow at higher elevations. The harsh winter in 2022 brought a lot of snow, which began melting as I was starting my trip.

The hiking season ends around early June in the Himalayas, when the monsoon starts. Throughout the whole traverse I was hoping to get as far as possible into my journey before the start of the monsoon. Monsoon season means not only flooding rivers, but also landslides that cause logistic issues for resupply.

Half the time I found myself camping in remote places, eating my own food; for the rest I had to rely on locals for food. Some people do ‘section hikes’ and then travel back and forth to Kathmandu for resupplies whenever possible. For me, that was not an option, as it would have been very time consuming, and I also liked the idea of staying in the wild without interrupting my trip. In the ultrarunning world there is a saying “be aware of the chair”. Once you feel the temptation to sit down and rest, it can be hard to get back out there!

The maximum amount of food I carried with me was for 12 days, which coincided with the longest sections without resupplies. This was the most I was physically able to carry considering the elevation was often above 5000 meters (16,000+ feet), and I was also carrying mountaineering equipment and extra gear.

Throughout the traverse I heavily relied on locals to feed me and supplement the food I carried. Commonly, locals eat Dahl Bat, a rice dish with lentils and potatoes; rarely meat, maybe some eggs. One thing that is widely available and easy to pack are cookies. I never ate so many cookies in my entire life. Locals would sometimes make a kind of flat bread called Roti that I would eat with cookies.

Another thing that is widely available in the Tibetan community is Tsampa, a kind of porridge made from roasted barley flour. The first time I tried it, it felt like eating dry flour and it got stuck in my mouth. Later, I learned that locals mix it with sugar, water and yak butter. Then it becomes actually quite tasty. Yak butter and sugar is how many locals get their calories.

In total, I met 3 times with a porter who brought resupplies that I had stored in Kathmandu, both food and gear. For example, in Makalu Base Camp, I needed a 200m rope that would have been way too heavy to carry the entire way.

Meeting up with the porter was logistically quite interesting, as it would take the porter many days to reach me, and there were times when I was afraid that we would miss each other.

At every resupply, I received 12 days of food from the porter. This totaled 48 day’s worth of food (including what I started out with), which covered about half of the total required food. For the remaining days I completely relied on local food.

Another side of logistics is consumable gear, like gas canisters for cooking, which are hard to find outside of Kathmandu. Before I left, I did a lot of testing and figured out that I could use one gas canister for roughly 12 days, when using it as sparingly as possible. Gas canisters were also part of the three resupplies mentioned.

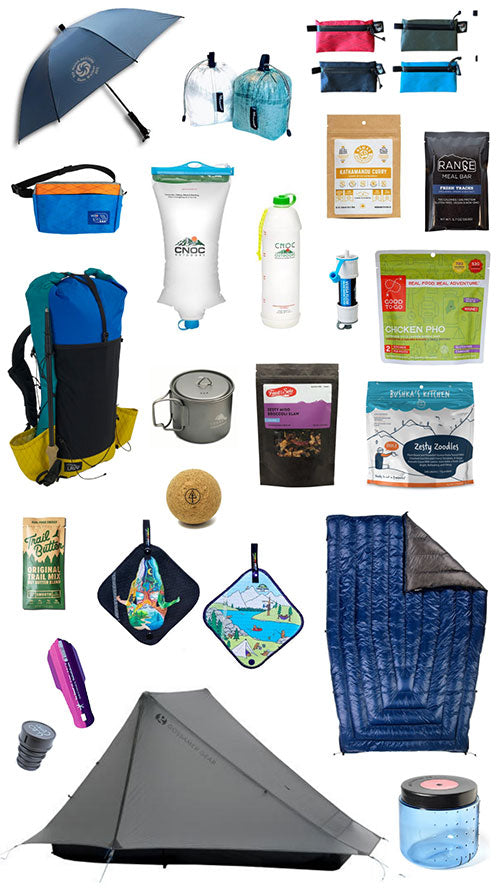

Gear plays an important role in any expedition. A Middus 1p in DCF and a Framus 58L Ultra 200 backpack, were used. What was your average and max pack load, and why did you decide to go ultralight on some of your gear choices? How did it affect the journey?

In general, it is pretty safe to say that everyone likes to travel as light as possible. But I think there is a limit when ‘ultralight’ gear sacrifices too much and becomes ‘stupid-light’. For example, when waterproof layers become so thin that they do not protect against rain and hypothermia anymore. Given that the GHT is very unforgiving with gear, I did not want to make that mistake.

I started with 28 kg (62 lbs) with 12 days of food. I was really pushing the Framus 58L pack to the limit, but it held up incredibly well.

The East of Nepal is where the technical parts are, and as I moved to the West, the passes got less technical and lower in elevation, so my pack got lighter and lighter. I could leave heavier gear behind as I went on, so in the end, my pack weight averaged around 16 kg (35 lbs) — not ultralight by any means, but with ropes and all the equipment needed for this remote traverse, there are many things you just cannot get rid of.

Ultralight meant that I was able to cover longer distances in a shorter period of time. For my trip that was essential, as it allowed me to complete the traverse before the monsoon got really bad, and also before my visa expired.

In the West of Nepal, which is usually quite dry, when the monsoon arrives the water level in the rivers rises easily by 1-2 meters, and the lack of bridges can make them impossible to pass.

To the best of my knowledge, I might be one of the first solo travelers to cover the entire GHT high route in one season. Ultralight gear was definitely part of the equation. I could have gone lighter by bringing less food, but I needed some extra margin knowing how many calories are needed to keep warm at altitude.

I was really surprised about the comfort of the Framus 58L. Even pushing it out of its designed carry load, I found it to be as comfortable as frameless packs with a standard 5 kg (11 lbs) base weight. The backpack is not only lightweight but highly water resistant, so in conjunction with DCF drybags I could keep everything dry. Through rain and snow, I was just amazed how dry the pack remained on the inside compared to standard nylon packs. It performed much better than previous packs I’ve had.

On a funny note, it is curious that after so many days of not showering, and containing all my dirty gear, the backpack still smells like the new Ultra 200 material. This is in stark contrast to other backpacks that take on the smell of dirty clothes and food after long thru-hikes.

What was the hardest part of the trek, mentally or physically?

Having started in the East right after winter, I was very concerned about the first 5000 m pass, called Lumba Sumba. Since it connects the Kanchenjunga area with the Makalu national park, I knew that if I could not make it through, a long detour would be required. The approach to the pass takes about a week, and on the other side, it takes another week to get to the first resupply.

Not making it over the Lumba Sumba pass would mean barely making it with enough food. Due to Covid, no one had gone through the area in the past few years, so I was quite worried.

I was very relieved when I arrived at the foot of the pass in the afternoon, even if I sank into the soft snow down to my hips. Post holing in deep snow at that elevation was extremely exhausting, so instead I waited, waking up early in the morning at 2am to take advantage of the frozen snow. I felt a bit like Jesus walking over water, just that in my case it was snow!

This was an important day, as from there on I knew that the next mountain passes would have more technical difficulties, but I had also successfully passed one of the most challenging ones in difficult weather conditions.

There are three technical passes in the East that are above 6000m, with 40-degree slopes requiring proper mountaineering gear like crampons and an ice axe. Here, you are in contact with hard packed blue ice, climbing down rocks and navigating through a labyrinth of crevassed glaciers.

For the rest of the hike, the main challenge was navigation. In many places the trail is not obvious, especially near rivers where it disappears every year during the monsoon season.

Any interesting stories to share?

I have hundreds of stories!

On one of the last mountain passes in the East, Gyanzen La (5500m), I felt so relaxed and confident after 80 days of travelling at high elevation. Then suddenly, within just a few minutes, the weather changed drastically and dropped 1 metre of snow that came out of nowhere — in a desert-like landscape. I was stunned. Staring at my GPS, trying to find the route, there was so much snow that I could not wipe the screen clear fast enough. It became a complete white out situation, very scary.

What made things worse is that at that time, I was not equipped with winter gear and was wearing trail running shoes and shorts. Until then, all had gone so well, I was almost finished with the GHT. But it was a strong reminder to remain alert, as if nature wanted to tell me “you are not done yet!”.

Any suggestions for someone planning to venture on the Great Himalayan Trail?

The GHT is really a different kind of trail. I have been on trails where one could cruise an average of 40-50 km a day. But on the GHT you have to lower your expectations. On my longest hiking day, 16 hours, I only managed to cover 5km, crossing a glacier that was reminiscent of a loose boulder field.

There is a lot of route-finding and river crossings that slow you down a lot, as you constantly have to figure out where to go next. There is beauty and enjoyment in it, and sometimes also frustration; so one needs to like that challenge.

Also, there is a community of people online that I recommend reaching out to. Everyone I contacted for information has been very kind and helpful.

This article originally appeared on the Bonfus website. A huge thanks to Bonfus for permission to share this article and adventure with you all here on GGG!

6 comments

Amy Hatch

Hi Brandon, thanks for your comment, and great point! Linking this article to the Bonfus pages now : ) Thanks for catching that. Amy

Brandon G

Fantastic journey. Thank you for sharing and inspiring us. Most interesting story I’ve read on GGG. Your reliance and humility with the locals you encountered was fascinating, balanced against your grit and incredible competence in the mountains. Reminded me of the book The Places In Between by Rory Stewart, as he chronicled his walk across Afghanistan in 2002.

Also, GGG should link this story on their page for the Bonfus Framus.

Sahra

Thank you for such a fascinating read. I am planning on doing the trek in five years, when I turn thirty. I’m hoping to find a partner to trek with, being I am a very petite woman and would feel safer this way, but if I don’t, so be it. I have done hikes of similar length and time alone. My heart cannot be held back any longer.

Thank you for inspiring me just a little bit more.

Matthias Ekman

@Eric B: Thank you for your kind words, very nice for me to hear. Appreciate it. @Corinna: It is just a cheap noname $15 panel that worked fine. For the last section in the West (Dolpa, Humla, Simikot) I knew that it would be very difficult to get power, so I had pre-arranged to switch to a more reliable (but also more heavy) panel from Sunnybag called Leaf Mini. But honestly, they both worked okay.

Corinna

What solar panel is that?

Eric B.

A great saga of a trek only for the very fit and very experienced backpackers. Thanks.

I’m now in my late 70s so UL and SUL backpacking gear is necessary for me to continue backpacking here in the US mountain west. But tough as some days are they are almost always worth the effort, as this story underlines. It also emphasizes that along with the proper gear you need proper skills and fitness to safely accomplish grand treks.