Tumbles saw the sign from the back seat of a car. “Pack Llamas For Rent,” it read, and he managed to jot down the number before it vanished out of sight. I was skeptical — everyone in our trail family was. We were a bunch of dirty thru-hikers a couple months into the Continental Divide Trail with steadily declining bank accounts. There was just no way, right?

1. Meet The Llamas

A few days later, Tim from West Elk Pack Llamas was pulling up with a trailer full of camelids. As a fellow thru-hiker, he’d cut us a deal. He introduced us to Pete and Chavano, our llama companions for the next few days. We patted them on their long necks and they gave us alien looks, as if to say, “What do you think you’re doing?”

Tim took us through all that we’d need to know. They’ll eat pretty much anything green, they drink out of streams, they can carry about 60 pounds each, (more when they’re in better shape), and generally, they’re super easy to take care of. He taught us to saddle them correctly, and we arranged to meet him in a couple days at Monarch Pass. There, we’d take Pete and Chavano and get hiking. We couldn’t quite believe it would be that easy.

2. Go at the Llamas’ Pace, Not Your Own!

Llamas aren’t the best conversationalists, and they don’t contribute much to planning, so the bulk of it will fall to you. I’d advise two major considerations when thinking about your own trip with your own llama pals.

You may not want to spend too much time above tree line. Llamas have fantastic eyesight, and they’re natural livestock guardians. Often, they’ll spy movement down in the valley and they’ll stop, alert. I imagined them thinking, “What the hell was that?” every time they did this to us, and they did it a lot. We were hiking along the Collegiate West in Colorado, so we spent almost all of our time above the trees.

Think about how far you want to go with them, too. They’ll top out at around 2 miles per hour and 10 miles per day. That’s a perfectly enjoyable pace for a backpacking trip, but for us it was frustratingly slow. I would still recommend llama-blazing to other thru-hikers, though, with the right attitude. It’s a perfect, leisurely interlude to the rest of your hike — go at the llamas’ pace, not your own!

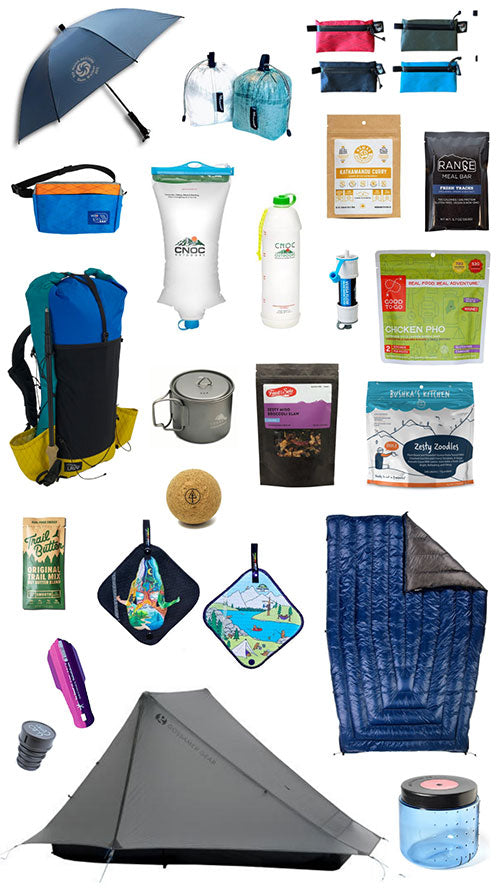

3. Fully Utilize The Llamas’ Carrying Capacity

If a relaxed pace doesn’t sound like what you’re looking for, I can change your mind with two words: food capacity. A few of the things we packed out with our llamas: frozen hamburger patties, glass jars of salsa, real French Press coffee, and not one but two cast-iron skillets. All of you on the ultralight side of things know how insane that is. We ate like royalty. After months on trail eating mediocre-at-best food, we were putting meat back onto our bones. For once, a surplus of calories!

After a season of hiking, a single adult male llama can carry up to 80 or even 90 pounds. This opens so many doors for backpacking it’s almost stupid. Also, you have to take at least two llamas out at a time. They get lonely otherwise, which means double the carrying capacity for you. Have them carry your gear, extra clothes, as many warm, dry socks as you want! The possibilities are limitless.

4. Take Care of The Llamas

Even though they’re literally beasts of burden, they still deserve your respect. I actually got quite attached to Pete and Chavano. When we stopped for breaks, we would often just stare at them while they ate their grass. Sometimes one of the llamas and I would share a look, both of us thinking, “What is this strange animal doing?” They never spit at us, only each other.

When you saddle them up, make sure to do it with love. Brush off their fur so that there’s no irritation, and be careful to tie the front strap onto the sternum rather than the stomach. That’s where most of the weight will be. When you stake them out at camp, try to do it where they’re not likely to get tangled up but still have a diverse buffet of green stuff to eat.

5. Don’t Show Weakness to Llamas

We were fighting Pete and Chavano every step of the way. We only made it about 4 miles the first afternoon hiking. They’d stop seemingly whenever they wanted to. We would pull gently on the lead rope, not wanting to hurt them, but they didn’t seem to care.

The second day, first thing in the morning, we tried to lead Pete and Chavano up a gentle slope. They refused. We begged. They did not listen. We pulled, but they would not budge. Rain came and we retreated for cover, realizing they were perfectly happy to go backwards! (This felt like a slap in the face.)

The weather passed over us and we tried again, but as we approached the hill, those two jerks stopped in their tracks once more. Desperate, we called Tim with the small amount of phone service we had left. His advice was to “tie ‘em together and slap ‘em on the ass.” We did, and it worked! That became our go-to strategy, though it was still imperfect.

When I consulted Tim after the trip on why they fought us, he said he thinks Pete and Chavano just don’t like each other. Different llamas are always beefing, even on the farm. They tend to have hierarchies, too. One might like to be in the front of the group while another might refuse the same position. It might have just been a case of two big personalities clashing.

I have a sneaking suspicion, though, that they knew we were soft. They were more stubborn than us, often winning out in our power struggle. They grazed when they wanted and dictated most of the breaks.

6. Become One With The Llamas

I remember approaching a snowy pass with Pete and Chavano. It was a little intimidating — we were postholing, sinking almost to our knees. The sun had done its work on the snow throughout the day, leaving it slushy and unpleasant. I couldn't help but wonder how the llamas would do. I certainly didn’t want to see one of them slip.

I was impressed when they plowed through the snow, keeping their balance perfectly, following Tumbles through the drifts. I thought about how incredible llamas are as alpine pack animals, their history alongside humans. They seemed sure-footed. I thought about the llamas’ padded feet, how they don’t tear up alpine ecosystems the way horses’ hooves might. They seemed made for this.

I had a distinct sense of pride hiking alongside them. I thought we cut a striking image–intrepid mountaineers alongside our animals, capable of surmounting any obstacle. Our feet beat in time with each other.

7. Learn From The Llamas

On the last day, Chavano decided he was done. We were about two miles from Cottonwood Pass, where we’d arranged for Tim to come and retrieve his llamas, but evidently we had done something wrong enough to really, really piss off Chavano. He sat down out of protest and wouldn’t get back up.

We tried unclipping them from each other and leading Pete separately down the mountain, hoping Chavano would follow. We tried removing Chavano’s saddlebags. We tried clipping Pete in front of Chavano and urging Pete on, but Pete remained stock still in solidarity. We talked to Chavano. We begged. We pleaded. He didn’t care.

After maybe two hours, Tumbles and I sat down with him and resigned ourselves to our fate. Rain clouds were coming our way yet again, but there wasn’t much we could do. Maybe if we had paid more attention along the way, maybe if we had adopted the patience, the pace of our llamas, it wouldn’t have come to this point. Our human urge to rush had backfired on us. We should’ve been more like them.

Eventually, Tim hiked up the hill to bail us out. He checked what we might be doing wrong, and he did point out that Chavano’s panniers were hanging a little low. This shouldn’t have been enough to annoy him to this extent, so maybe it was just the straw that broke the camelid’s back.

Tim got low and heaved on Chavano’s lead like a man possessed — farmer’s strength. Chavano was up, as if he knew Tim meant business. Tim dragged him the rest of the way down the pass, lecturing him all the while, and then loaded Pete and Chavano into the trailer. We said our good-byes, our thank yous, and they were off.

I remember watching them go as the sun set over Cottonwood Pass, feeling humbled. What could I control? I couldn’t even control a llama.

Matthew Kok is an essayist, a poet, a traveler, and absolutely in love with the world outside. They are currently operating out of Manapouri, a little town in Aotearoa–South Island, New Zealand. You can find them curled up with Stormy the housecat or cooking up big, elaborate breakfasts late in the morning. You can also find them on Instagram at @matt.kok

2 comments

Lynne Connelley

We are retired in beautiful Bend, OR from our jobs and also from professional llama packing. Your article is the best I’ve ever read on llama packing. We are down to two aged llamas, have lost our three lead llamas over the past years (one just last fall) and so miss life on the trail with the boys. One of my favorite pix is a llama looking over my husband’s shoulder at a trail crossing while they studied the map together. He was clearly thinking that Ed had no idea where we were or what he was doing. Priceless. Your article was fabulous. Thank you

Janet A

A pack of Llamas tote supplies to LeConte Lodge, on the top of Mt. LeConte in the Smokies. It’s always a treat to pass them on the trail. They are able to carry a lot of weight with minimal impact on the trail.