Picture this scenario: You’re out on a multi-day hike in the backcountry and have been above treeline for some time. The ridge has offered gorgeous views of the surrounding range, but anxiety starts to set in as you realize the dark storm clouds in the distance have started migrating your direction. You checked the weather before you set off for the day, but it seems the lightning and rolling thunder is approaching quicker than you anticipated, and you won’t be able to make it to where you planned to settle down for the night before it is upon you. What do you do?

I’ve had numerous occasions just like this one while recreating in the backcountry, and still others that have been even worse — trust me when I say, there’s no worse feeling than waking up in the middle of the night to realize you picked the tallest tree to camp under, just as the height of a storm is bearing down.

Oftentimes storm safety doesn’t cross hikers’ minds until they’re in the grasp of one, and even then recollection on proper procedures can be fuzzy. As helpless as you may feel in the moment, there are steps that you can take to mitigate your risk of being struck.

Unfortunately, there are also plenty of misconceptions, along with plenty of misinformation, around basic storm safety, some of which can actually increase your risk. So, let’s set the record straight and dig into the Dos and Don'ts of lightning safety in the backcountry.

DO check the weather and set turnaround times before venturing into the backcountry, and stay up-to-date with forecast changes during your trip. Turnaround times will get you off of exposed summits before it’s too late.

DO turn around and head back if you hear thunder. Also, make sure you have a backup plan for slackpacking, and don’t wait until the storm hits to start worrying about lightning safety. NOTE: Tell someone your plan and have a personal GPS device handy just in case of an incident.

DON’T assume you’re safe because it’s not raining. Lightning is unpredictable and can strike over 3 miles from the storm clouds themselves. In rare cases, lightning has been recorded striking over 10 miles from their thunderstorm origins. Best practice is to wait 30 minutes after you last heard thunder before you continue recreating.

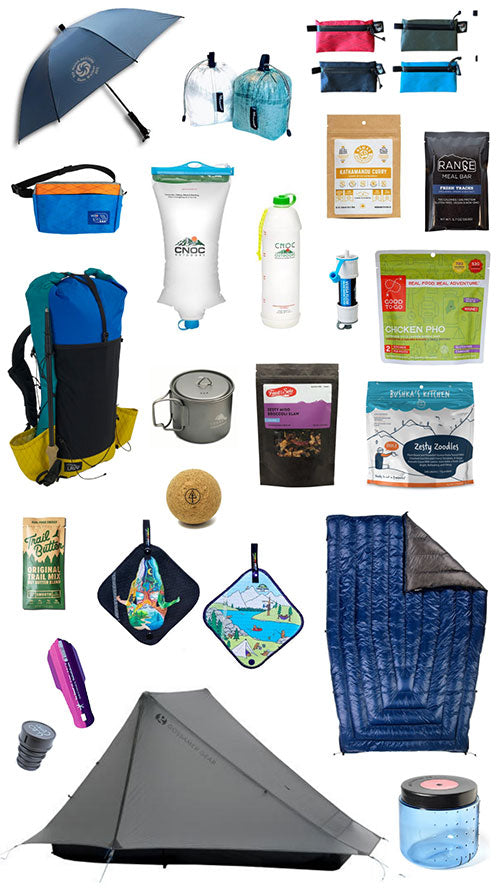

DO choose an appropriate spot to hunker down. If you don’t have the option of returning to your car or finding a close shelter, avoid peaks, exposed ridges, and higher ground. Spread out your group and set up in a depression or valley. You should be below treeline but be sure to avoid tall, isolated trees. Take all of this into account if you’re setting up camp and anticipating a storm rolling in over night.

DON’T assume you’re safe from a strike in a lean-to shelter. Of course this article is about the backcountry, but if you are on a trail with shelters, lean-tos or warming huts (such as the AT), these may be your best option for getting out of a storm. That said, it’s definitely worth mentioning, lightning strikes can still happen in these shelters. Hunkering down in a town or proper four-sided building is a better option, if available.

Note: If you choose to stay in a shelter, DO assume the lightning position and avoid windows and the open side.

DON’T assume a tent is a safe place to take shelter. Tents offer no protection from lightning strikes. They can actually increase your risk, if you’re camped in an exposed area where the tent is the highest point.

DON’T take shelter under tall objects. Tall objects such as trees or fire towers are more likely to be struck, and ground currents can be dangerous to those in the vicinity.

NOTE: Lightning may be most attracted to tall objects, but that doesn’t mean those are the only places it will strike. The safest place to take shelter is indoors in a town.

DO assume lightning position. Do not lie down. Instead, crouch down with your weight on the balls of your feet, your feet together, and your head down with ears covered. The goal is to get as low and balled-up as possible without being prone. Crouch on insulated objects such as a sleeping pad, backpack, or clothes bag. Whether rushing below treeline during a midday storm or waking up to flashes of lightning in the middle of the night, this is the safest position you can assume when ideal shelter is not available.

DO be prepared to give first aid to someone in case of a strike. The human body doesn’t store electricity so it’s perfectly safe to give someone first aid that has been struck by lightning. Be prepared to call 911, use an emergency signal, perform CPR with rescue breathing, or treat for shock if someone is struck.

Hopefully you won’t walk away from this article with a fear of storms in the backcountry. The chances of actually being struck are extremely low and the chances of severe injury are lower still. These tips are here to help you minimize your risk in an exposed situation and feel educated about the proper steps to take when a storm descends while hiking, backpacking or otherwise exploring wild places.

So, stay safe and happy hiking!

Katie got bit by the thru-hiking bug in 2019 after completing a thru-hike of the AT. She met her partner at the NY/NJ border and rescued her husky, Thru, while on trail in VA. Since she has hiked the CT and LSHT and hopes to complete the Long Trail in 2021 and hit 10,000 miles by 25.

IG: @mosspetal

Website: www.thethrucrew.com

Article Sources:

- https://appalachiantrail.org/explore/plan-and-prepare/hiking-basics/safety/lightning-safety-on-the-appalachian-trail/

- https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/lightning/safetytips.html

- https://www.cmc.org/Portals/0/GoverningDocs/NOLS%20Lightning%20Safety%20Guidelines.pdf

- https://americanhiking.org/resources/lightning-safety/

1 comment

Doug

The “lightning position” sounds great but it is not possible for many people, especially to maintain for the duration of a storm. The most important part of it, which is very easy to do, is to keep your contact points with the ground (your feet) close together. This reduces the difference in electric potential between the two feet so it is less likely current would go up one leg and down the other. Many more people are killed by ground conductance than by direct strikes. This principles holds even if you are inside a shelter or mountain hut.